|

In the first few centuries after the death of Jesus, there was much debate in the nascent Christian community on whether or not imagery should have a place within Christian worship (Mullett). These internal deliberations, coupled with the growing tensions between Christians and the Roman pagan majority of the empire, meant that for many early Christians, visual manifestations of their faith was not standard practice. It is to this period before 313 CE, that most scholars point to when discussing the first emergence of identifiable Christian art (Mullett). Often cited as “pagan in style and Christian in subject”, the Christian art from this era is largely symbolic and appropriative of pagan motifs- so that often it is only the context of the work, which allows it to be identified as Christian (Hood 5) (Stokstad 16). Yet, several extant examples show the beginnings of the vibrant visual culture that would eventually develop and evolve into the canon of Christian art which we know today. One such example can be found in The Good Shepherd fresco which decorated the domed ceiling of the Priscilla Catacomb in Rome. Pulling from Classical motifs, The Good Shepherd is presented with the stylistic tenants of Late Antiquity, yet also works to showcase the incipient symbolism that was developing for the newly emergent religion, by creating images which contemporary Romans and newly converted Christians could relate to.

1 Comment

Since antiquity, art has been used to inspire, influence, and direct the minds of its viewers towards its creator's aim. Yet within the canon of art, no motif can be said to be more persuasive than depictions of war and military encounters, which often had the power to subdue or inflame depending on how each artist chose to represent their subject. Whether through the creation of propaganda or in the act of documenting the realities of war, artists and patrons have sought to give their struggles voice and to create narratives which still live on today. On this account, both Diego Velázquez's Surrender of Breda and Fransisco Goya's The Third of May 1808 distinguish themselves- not only for their individually singular approaches to war in their own times but also by how they have shaped the overall artistic wartime narratives. When placed side by side, these works not only present two sides of the spectrum of war imagery, from the civilized engagement of The Surrender of Breda to the expressive violence in The Third of May 1808, but they also work to relate the changing shape of Spanish identity and artistic practice. When looking at the visual history of the Greek civilization there is a distinct shift in the portrayal of form, from the stylized roots of the Mycenaean and Minoan traditions to the naturalism which took hold during the Classical Era. This can be seen when comparing the terracotta figurine Bell Idol, created circa 700 BCE¹, to the later classical work Bronze Statuette of Athena Flying Her Owl (herein referred to as Bronze Athena) which dates back to circa 460 BCE². Set apart by both time and location, originating from Thebes (Boeotia) and Athens respectively, both sculptures work to illustrate the evolution of Greek canon. Yet by examining these two pieces, it becomes clear that despite their divergences and stylistic range, both the Bell Idol and Bronze Athena share similar aspects which are illustrative of Greek cultural values.

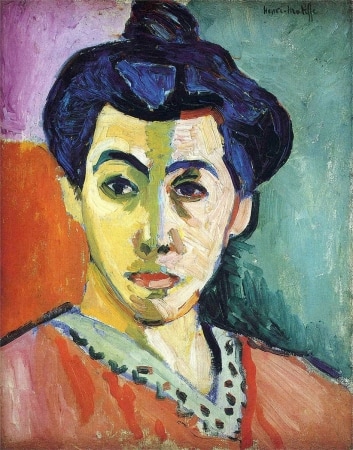

The early 20th century brought with it many social, political and technological changes. The world was changing and as a result the artists and artworks of the time changed with it. This was especially true of Germany, where an expanding empire, rapid industrialization and prewar anxieties manifested in several unique artistic movements which are often categorized under the larger umbrella known as German Expressionism. One artist working during this time was Wassily Kandinsky, whose non-figurative work pushed the boundaries of form. In his 1912 painting, Improvisation No. 28, Kandinsky sought to express both his own philosophy and to engage whomever might view his work. Kandinsky was a founding member of the Der Blaue Reiter Group along with Franz Marc and Gabriele Münter. An offshoot of the German Expressionist movement, the Der Blaue Reiter Group looked to the prewar society prior to World War I in Germany and saw it lacking. The rise of industrialization and growing urbanization cultivated a sense of alienation in the members of the Der Blaue Reiter Group, who sought to alleviate their isolation through the expressive power of their art. Works like Kandinsky's Improvisation No. 28 worked to convey this underlying philosophy of the Der Blauer Reiter, turning away from the industrialization of the age and instead focusing their attention upon the organic, innate ability of an artist to disclose their own personal expression. Vibrant and graphic, Henri Matisse's Portrait of Madame Matisse (The Green Stripe) built upon the previous work of the Impressionists and Post- Impressionists and helped articulate the voice of a new movement, Fauvism. Spanning only a short time, Fauvism was an artistic movement in France from 1904 to 1908 that was marked by its bold and expressive use of color and simplification of shape. Painted in 1905, near the height of this short lived movement, Portrait of Madame Matisse (The Green Stripe) serves to illustrate the main stylistic hallmarks of the Fauvist movement even as it works to divorce itself from the academic stylings of the past.

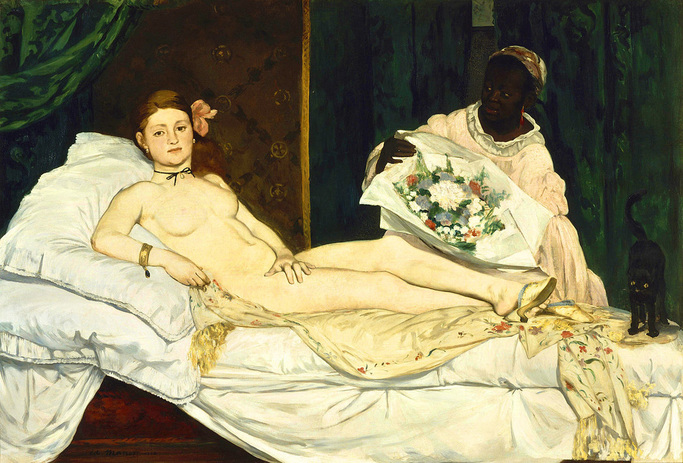

Ambiguous Spaces & the Artistic Legacy of Modernity As a part of a constant continuum, the history of art can be seen as a large tapestry where upon tugging one thread, another responds - such is the intrinsic interwoven network of artists, their influences and their impacts upon the cloth as a whole. Motifs, subject matters and styles spread across the surface like different colors, popping up here and there, moving through time as a slow gradation bursts into a bright splash of color. Similarly, although they lived two centuries apart, the connection of 16th century Baroque painter Diego Velázquez's work to that of 19th century Realist Éduoard Manet's is undeniable. Each artist found themselves caught in the shades and reflections of the shifting societies that they were a part of - Velázquez in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and the Roman Catholic Church's subsequent Counter Reformation, and Manet working in the shadow of the revolutions and social upheavals which had gripped France for almost a century following the infamous French Revolution. Yet both Manet and Velásquez brought innovation to their works in spite of, or even maybe as a direct result of these social changes. It was Velásquez's loose impasto brushwork which paved the way for Manet's break from the academic painting into taches of color and graphic line. Though their career paths differed greatly, towards the end of their lives both artists chose to explore the medium and meaning of painting, expanding on their own roles as artists. Known as two of the most enigmatic paintings in art history, Las Meniñas by Diego Velázquez and A Bar at the Folies-Bergère by Éduoard Manet both present the viewer with paradoxical spaces through which the artists seek to examine the subject of gaze and painterly purpose within the concept of an ever-shifting genre scene.

As one of the most controversial paintings in the history of art, Éduoard Manet's Olympia caused quite a stir when it was shown in the 1865 Salon in Paris. Though he built on the foundations of the classical nude in his depiction, Manet brought his subject matter into the 19th century and eschewed the traditional methods of painting. Instead, working in his own manner, Manet created a style which was wholly his own, which despite the jeers of his critics, worked to inspire his contemporaries and helped to shape a movement that would change the face of art. |

AuthorCrystal has a MA in the History of Art from Courtauld Institute of Art as well as a BFA in Art History from the Academy of Art University. Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed