|

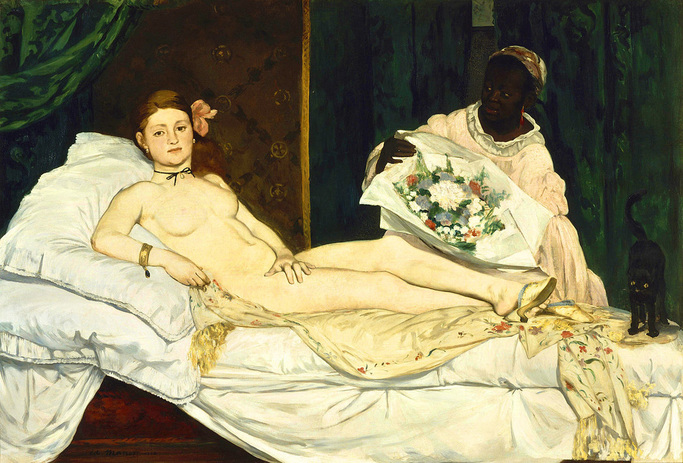

As one of the most controversial paintings in the history of art, Éduoard Manet's Olympia caused quite a stir when it was shown in the 1865 Salon in Paris. Though he built on the foundations of the classical nude in his depiction, Manet brought his subject matter into the 19th century and eschewed the traditional methods of painting. Instead, working in his own manner, Manet created a style which was wholly his own, which despite the jeers of his critics, worked to inspire his contemporaries and helped to shape a movement that would change the face of art. Manet was born into an upper bourgeoisie family during a time when France was still in the midst of several smaller revolutions following the destruction of the Napoleonic Empire. As such, Manet lived in a time when France was making its way slowly into modernity with the industrialization of Paris, the formation of an elected General Assembly, universal manhood suffrage and France's transition from the Orleanist Monarchy to the Second Empire to the Third Republic. So too was the art of France changing. Though many artists still clung to classical subjects and the Grand Manner style of painting, others, like Gustave Courbet, were turning to more common day subjects and scenes of everyday life. Manet was swept up in this trend of Realism as well and sought to depict ordinary people and contemporary subjects. However unlike Courbet and other Realists, Manet also used his everyday subjects to critique the motifs and themes that were upheld in art - as well as used the subject matter as a point of departure for his technique. One such painting was his reinterpretation of the classical motif of Venus as a prostitute titled Olympia. Though Manet painted Olympia in 1863, he didn't submit it to the Salon until a few years later – possibly due to the reception of his painting Dejeuner sur L'herbe or Luncheon on the Grass which was not only rejected from the 1863 Salon, but also ridiculed by the public. Olympia came onto the scene in 1865 and caused a scandal amongst the art world. Olympia (a common working name for a prostitute in 19th century France) lounges on a disheveled bed, naked except for a few adornments at her wrist, neck and feet, with a servant in attendance and an angry hissing cat at her feet. The pose is almost directly taken from Titan's Renaissance painting Venus of Urbino, echoing the lounge of Titan's Venus's body and the placement of her hand. But where Titan's Venus is modest and meek, Manet's Olympia is direct and faces the viewer with a blunt expression on her face. The sprawl of Olympia also referenced several other works which Manet (and the public) was aware of at the time of painting, from Goya's La Maja Desdenuda to Ingres 's and Fortunay's odalisque paintings which depicted light skinned Turkish concubines attended by dark skinned slaves. Manet's combination of these three motifs, along with his placement of the subject into a modern day setting worked to build upon and comment on the history of the female nude within the context of art. Gone was the Venus and other acceptable nude motifs from the classical or allegorical stories that most artists chose to depict, instead here was a scene from the darker edges of society- something polite society didn't talk about- the 'modern Venus' blandly confronting her viewers (Gardner 670). At the time it was common for men to visit prostitutes and have mistresses greet them, in much of the same manner as Olympia greets the viewer. Yet to have it displayed in public at a Salon in front of all Paris was shocking. The directness of Olympia's gaze also worked to turn the concept of the male gaze on its head. This was not some unknowing beauty subject to the voyeuristic tendencies of painter and viewer, but a woman who knew she was being looked upon, confident in her sexuality. The inclusion of the black maid offering Olympia flowers from a client, at the time, was also taken as an allusion to animal sexuality – something which was echoed in the cat who glares out at the viewer. The reaction of the public to this perceived vulgarity was so severe that the painting had to be rehung higher in the Salon gallery and attended by guards, as so to avoid physical attacks. Not only did the critics and public rip into Manet's subject matter, but they also found much to criticize with Manet's technique. Manet, drawn to the call of Realism and inspired by the works of Courbet, also sought to portray his figures and process in a realistic manner. He painted from life, always having his subject in front of him. As a result his figures were not the idealized ones seen in the paintings done in the style of the Grand Manner but accurate representations of life. The natural curves of flesh and fat can be seen in Olympia's body, from the dip in her stomach to the shift in her leg as it crosses the other. Her breasts have weight, her body pushes into the cushions and her hand does not delicately cover her genitalia (as was common in the Venus Pudica pose) but rests there, taking the weight from her arm. Manet also allowed his paint to read as paint upon his canvases, forsaking the illusion that had largely been the style since the Renaissance. With large quick brushstrokes and often abrupt transitions from light to dark, Manet created a new style of painting which departed from those of his teachers . Foregoing the painstakingly built up of layers of his predecessors Manet worked alla prima or wet on wet with his oils- not allowing the painting to dry before he finished rendering his composition . In order to get everything down within one sitting, Manet often would simplify what he saw in order to articulate it onto his canvas. This technique allowed him to work more quickly with more expressive brushstrokes, as can be seen in certain details of Olympia such as the patterns of the curtains, the form of the cat or the shadows of the pillows. These visible brush strokes drew much criticism from both the public and art critics at the time but served to greatly inspire some of his younger contemporaries who would form the group know as the Impressionists.

Another result of Manet's new style and technique was the flattening of form and space within his works. Eschewing the gradual transitions and cleanly defined forms, Manet allowed flat sections of color to exist within his works creating graphic intersections of light and dark. This can been seen in Olympia's torso and arms where the white of her skin stands in stark contrast to the almost outline of a shadow in the space between her arm and her body. However upon closer inspection in these flat sections of color, Manet's brushstrokes take up the job of defining the form. Using curvilinear lines Manet contours the shape of Olympia's body, letting the viewer see the surface of her body not through shading, but in the application of the paint. This mixture of using both three and two dimensionality within his work helped Manet to reinforce the physicality of paint as well as Olympia's form and helped to open up the art world to the exploration of the medium. Though critics of the time scoffed at these innovations, other artists such as Degas, Monet, Cezanne, Van Gogh and the other Impressionists took notice. Olympia represents a turning point in western art history. Reflecting the changes occurring within France, Manet's evolution of style showed a step towards the modern, earning him the title among many as the father of modernity. With Olympia, Manet not only presented an avant-garde approach to previously established motifs within the art world in regards to the female nude but also to the depiction of form both in its physicality and imperfections. His use of his medium was innovative and allowed for a looser, more graphic depiction of the human form and its surroundings. Even though it was vilified by both the critics and public alike, Olympia served to expand upon the already established school of Realism and to sow the seeds among Manet's contemporaries for the upcoming works of Impressionism. His ingenuity in both the content and application within his work serves to define Manet as one of the founding voices of modernism and an artist which helped to usher in the shifting views on the depiction of human form which would dominate the upcoming 20th century. Bibliography

Images from Wikimedia Commons

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCrystal has a MA in the History of Art from Courtauld Institute of Art as well as a BFA in Art History from the Academy of Art University. Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed