|

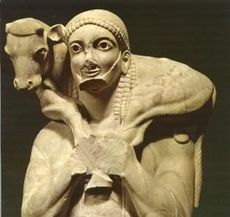

In the first few centuries after the death of Jesus, there was much debate in the nascent Christian community on whether or not imagery should have a place within Christian worship (Mullett). These internal deliberations, coupled with the growing tensions between Christians and the Roman pagan majority of the empire, meant that for many early Christians, visual manifestations of their faith was not standard practice. It is to this period before 313 CE, that most scholars point to when discussing the first emergence of identifiable Christian art (Mullett). Often cited as “pagan in style and Christian in subject”, the Christian art from this era is largely symbolic and appropriative of pagan motifs- so that often it is only the context of the work, which allows it to be identified as Christian (Hood 5) (Stokstad 16). Yet, several extant examples show the beginnings of the vibrant visual culture that would eventually develop and evolve into the canon of Christian art which we know today. One such example can be found in The Good Shepherd fresco which decorated the domed ceiling of the Priscilla Catacomb in Rome. Pulling from Classical motifs, The Good Shepherd is presented with the stylistic tenants of Late Antiquity, yet also works to showcase the incipient symbolism that was developing for the newly emergent religion, by creating images which contemporary Romans and newly converted Christians could relate to. Painted sometime near the end of the second century or in the beginning of the third, The Good Shepherd occupies the central medallion of the underground room known as the Cubiculum of the Veil located in the Catacomb of Priscilla, which was named after the portrait of a veiled woman who adorns a lunette in the same space (Harris & Zucker). In general, catacombs consisted of underground tunnels and rooms served as burial places for people of different faiths during Late Antiquity. However, they also became known, in particular, for manifesting one of the first Christian spaces (Maline 38). Decorated in typical the Roman fashion, using the ever popular Mediterranean decoration technique known as fresco, early Christian images such as the Good Shepherd were painted by applying pigments to wet plaster (Mulett). This technique didn't allow for deep darks or intense saturation but did help to create a soft pastel palette which compliments the pastoral scene. Christ is presented facing the viewer with a goat draped over his shoulders, in the pose which would come to be known as the “good shepherd” motif. Flanking him to either side are two goats, two trees, and two doves against a plain white background which coalesces into a symmetrical circular composition. Taking on a contrapposto stance, The Good Shepherd shows hallmark signs of Classical styles- from the attention to anatomy, to the Roman chiton that Jesus wears. The visual motif of a man with a ram or calf draped over his shoulders was not new at this time, and can be traced back to the pre-Archaic Greek figures of the “moschophoros”, the calf-bearer, or “kriophoros”, the ram-bearer (Kinney 10). Commonly associated with the Greek god Hermes, who ferried the dead and shepherded his followers, these pagan motifs found an eager audience within the new Christian practitioners - who often saw the parallels between the two divine figures (Kinney 10). Christ also enjoyed great associations with the mythological figure of Orpheus, the Greek musician who traveled to the underworld and back in an attempt to save his deceased wife. Orpheus was also presented a strong parallel due his role as a mythological figure who was known to have rejected paganism in exchange for monotheist beliefs (Huskinson 71). Visual manifestations of these connections can be seen illustrated by the presence of the pan pipe fastened at Christ's waist, and the abundance of animals which surround him, both of which bear many similarities to common depictions of the Greek musician at the time (Barker 48). Thus the representation of Christ in The Good Shepherd can be seen to pull directly from these Classical motifs, as well as semi-contemporary depictions of heroes, like the 1st century fresco of Theseus, which adorned the wall of M. Gavinus Rufus's villa in Pompeii. In terms of the pictorial environment, while the trees and ground plane allude to elements of a natural landscape- by and large, the space that Christ and the animals occupy is abstracted. The forms of the trees are abbreviated with quick patterned brushstrokes, while the animals are reduced down to simple forms with minimal shading. Christ himself seems to waver between the realistic shading of his face, and the abstracted graphic heavy use of outline that defines the shape of his outstretched arm. This divorce from the naturalism that was often associated with the Classical era, helps denote a conscious change on behalf of the new Christian dogma. Early Christians looked, not to the real world, but the spiritual world beyond for their salvation, and as a result, the need to accurately portray the physical world lessened. Instead Christians looked to symbols and imagery which connected to their unfolding sacred texts, liturgy, and the “deep truths of their religion” (Lamberton 511). Accordingly, The Good Shepherd was not only a visual representation of a shepherd or even of Christ, but an embodiment of the Logos and Christ's words from the Book of John - Ergo sum pastor bonus, “I am the good shepherd” (Kinney 10). Similarly, Christ's surroundings in The Good Shepherd fresco take on symbolic meanings, not only within the central medallion, but in the designs which encircle it as well. Encompassing the Good Shepherd is another larger circle program, broken up into four evenly spaced with half medallions that show a similar abstracted artistic approach. Connected vertically, above Christ's head and below his feet, are two half medallions that feature peacocks -which were known as symbols of eternity and the divine realm (Harris & Zucker). To either side of the Good Shepherd medallion, connected horizontally, are two half medallions occupied by depictions of quail -small birds which were known to wander the earth and thus were common representatives of the earthy realm (Harris & Zucker). With these four skirting elements, the early Christian artist placed The Good Shepherd at the visual and symbolic crossroads between the earthly and heavenly planes (Harris & Zucker). Alluding not only to the dual nature of Christ, as both a man and a son of God, this intersection also was symbolic of the road to salvation he offered –as it was through Christ's gentle guidance that his flock would pass from one world to the next. Looking back on the early centuries of Christianity, it is easy to say that there wasn't a distinct Christian style. It's true enough, that by and large the early Christians, when they did make art, looked to the pagan world around them for visual styles and motifs. However it could be said that their handling and symbolic associations help to lend a transformative quality to early Christian works. By making visual motifs like The Good Shepherd their own, Christians were not only able to 'hide' within plain sight, but also able to cultivate a rich symbolic visual language that would grow to become the basis for Christian canon. These sacred visual associations meant that, not only were appropriated motifs such as the Ram-bearer, Hermes, or Orpheus, made meaningful to early Christians, but that Christians could then also look could look at other pagan works and see these Christian associations then reflected back. Stylistically the slight abstraction presented in The Good Shepherd, both in the handling of form, as well as the lack of environment, help to foreshadow major markers of the Christian aesthetic which would dominate Europe throughout the next few hundred years. As it was, The Good Shepherd and other frescoes and works like it, served as the stepping stone of Christian artistic development, with great popularity in the 3rd century but quickly dying off at the end of the 4th as a new, stronger Christian artistic style took hold. Works Cited:

1 Comment

Ron

11/20/2022 04:13:25 am

I think, the catacomb of Priscilla with the Good Shepherd is the catacomb described in the novel "Quo Vadis ?" by Henryk Sienkiewicz, 1896:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCrystal has a MA in the History of Art from Courtauld Institute of Art as well as a BFA in Art History from the Academy of Art University. Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed