|

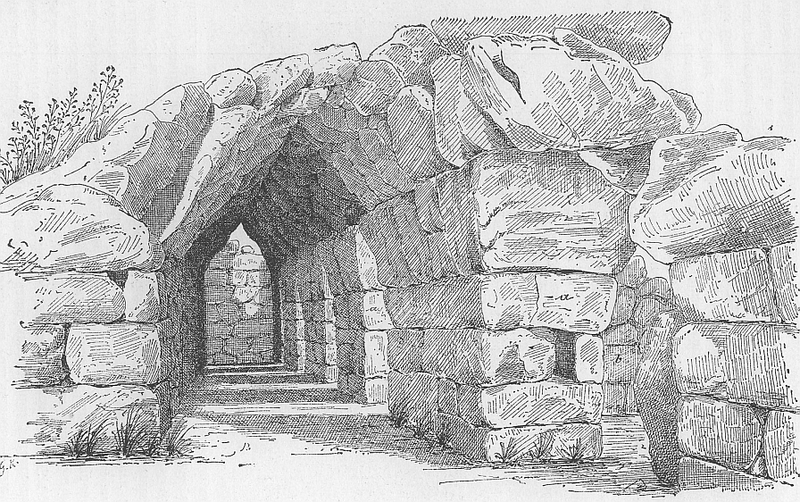

Sometimes all it takes is a thorough examination of the architecture and structures a society chooses to surround itself with to decipher the core values and concerns of that culture. When looking at the ancient world both the Mycenaeans and Minoans cultures prove illustrative of this point. Although they both served as precursors to the Greeks and showed signs of close ties in at least trade, the Mycenaeans and Minoan peoples differed vastly in how they approached trade, life and the creation of their culture. This is never more apparent then when comparing the remnants of the wandering grand palace of Knossos on Crete and the indomitable walls and ruins of the citadel of Tiryns located on the Greek mainland. The palace of Knossos on Crete serves as an example of the pinnacle of Minoan civilization and ingenuity. Rebuilt twice, Knossos was “a first among equals”- spanning 150,000 square feet and several stories, it was the largest of any of the palaces created by the Minoans. At the time of its first incarnation around 2000 BCE, the archeological evidence shows a Crete that wasn't united, with various distinct styles of craftsmanship spread across the island. As a reflection of this or maybe as a result, the first palace of Knossos possessed thicker walls and a bulkier footprint. However after its subsequent destruction (the cause of which remains unknown), the construction of the second palace occurred during a time of unification among the Minoans (circa 1700 BCE) and boasts an architectural style known for its light airy rooms, painted tapered columns, brightly colored frescos and lack of defensive walls. Centered around a large courtyard, Knossos spread out along corridors and clusters of rooms so intricate in nature that it inspired Sir Arthur Evans, the archeologist who led its excavation, to name the culture who built the palace after the legend of the Minotaur and King Minos's labyrinth. Yet, despite its mythological origins, the evidence uncovered at Knossos points to an innovative and carefree people, unburdened by war, with a complex urban society dedicated to the arts, religion and trade with the palace at its epicenter. In fact, many of the rooms within the palace were utilized as workshops where a majority of craftsman and artists plied their trade creating some of the major Minoan exports, such as olive oil, wine and pottery under the administration of the king. The advent of the written Minoan language is linked with the rise of the second palace and its economic boom - such was the amount of trade and need for written administrative records. Religion also seemed to be centered within the palace, for instance the large courtyard existing in the heart of Knossos is thought to be a place where “large scale semi-public religious ceremonies” were held. There were also smaller shrines scattered throughout Knossos including a small tripartite shrine south of the throne room that is often called the Central Palace Sanctuary and is believed to be the religious heart of the palace. The Mycenaeans came into prominence from 1600 to 1100 BCE. Though they were located on the Greek mainland much of their early architecture and art seems to have been influenced by the Minoans. Yet, unlike the Minoans, Mycenaean culture was rife with conflict and the competition. With the rise of the Mycenaean society came a wave of deforestation and over grazing which cause a large scale shift within the Greek landscape, making natural resources harder to come by and the Mycenaeans more reliant on trade. However Mycenaeans were also incredibly adaptive and collected ideas along with goods, innovating and combining them in their architecture and culture. The ruins of Tiryns provide a tell all, with its combination of Minoan-like citadels and large Hittite-like defenses. However it cannot be said that the Mycenaeans didn't manage to put their own unique twist on the towering fortifications. With a practice called Cyclopean masonry, the Mycenaeans proved their resourcefulness by cantilevering massive stones together to form arches and the structure for a barricading wall 20 feet thick, without the use of mortar. The site was so inspiring, later generations marveled that they could have only been built by giants. The people of Tiryns had good reasons for raising such monumental walls, because at the time of their construction around 1400 BCE mainland Greece was dominated by city-state warfare. Similar sites predating Tiryns, such as Malthi from Messia, had been razed and rebuilt as many as six consecutive times. A buffer for invading forces, the architects of the walls of Tiryns made sure its defenses could be used to their full advantage - intentionally routing walkways to expose enemies' unprotected sides and creating narrow galleries to bottleneck incoming armies. The large walls provided protection for those within the Mycenaean citadel and the assurance of safety for the king's people. The citadel itself was modeled on the sprawling palaces on Crete, yet served a very different purpose. Unlike Knossos which was a center-place of manufacturing, Tiryns seemed to mainly function as a port, trafficking goods from the sea to inland Greece along a series of complex roadways. This was reflected in the citadel, whose purpose was focused around the megaron, the throne room in which the king would accept visitors and traders. Smaller in size than the large courtyards of the Minoans, the megaron was usually occupied by a central hearth flanked by four columns supporting the roof and a throne from which the king conducted his business. Combined with the fortifications, the Mycenaean model at Tiryns can be pointed to as the precursor to the medieval castles that spread throughout Europe during the middle ages. Around 1450 BCE, a cataclysmic event befell the people of Knossos and caused the end of the of the Minoans. Not much is known about what brought about the end to this civilization, although there are many theories ranging from volcanic eruption to invasion. What is known is that for a short time afterwards the Mycenaeans took possession of Knossos (marking their presence with attempted repairs, tablets of Greek writing and simplified frescos) until its destruction in 1300 BCE. The citadel at Tiryns was similarly laid to waste around the same time period and although the strong walls remained standing for the next millennia, the site was eventually abandoned as a settlement in 470 BCE. Bibliography

Images from Wikipedia Commons

2 Comments

Lehys Gomez

1/24/2024 10:22:56 am

z

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCrystal has a MA in the History of Art from Courtauld Institute of Art as well as a BFA in Art History from the Academy of Art University. Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed