|

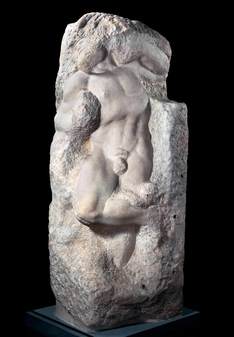

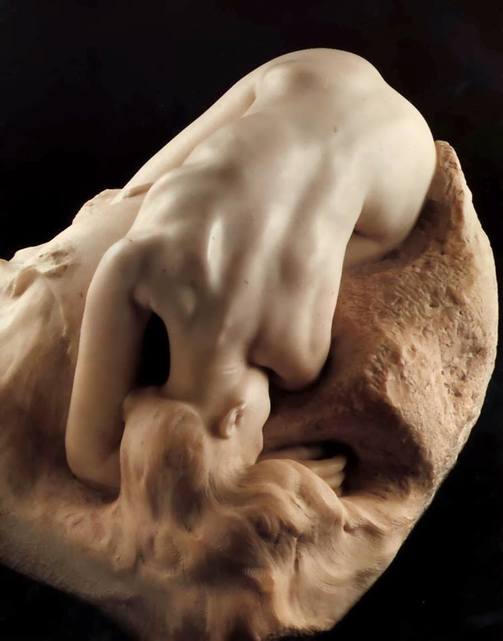

Auguste Rodin, who lived from 1840-1917, was premiere sculptor of the 19th century. Largely credited as the founding father of modernist sculpture, his pieces tended be explorations of human emotion, form and physicality. No matter his subject matter, be it mythological, allegorical or portraiture, Rodin sought to capture the human condition. His piece Danaïd (1889) exemplifies many of these aspects through his use of naturalistic form, contrasting texture, and scale. Originally modeled as a study for a piece of his large all encompassing Gates of Hell, Rodin chose instead to create Danaïd as a separate work (Blanchetière). Taking a subtractive approach, Rodin carved back the marble of Danaïd into careful curves and precise planes. Her form is a naturalistic one, neatly proportioned and created with clear understanding of anatomy. Her pose is somewhat unique when compared to the more famous stylings of the Renaissance or Antiquity, lacking the pageantry and gravitas that is so often associated with mythological subjects. Instead of a grandiose gesture or even a dramatic sprawl, Rodin has chosen to show Danaïd curled into herself, possibly overcome with despair or exhaustion. The smaller than life scale of the sculpture (which stands 36 x 71x 53 cm) helps to re-enforce the slight and desolate feel of Danaïd as she lays upon the stone. Yet Rodin's composition is without thought, in fact when viewed from above one can see that Danaïd creates a somewhat truncated S-curve. The twist of her torso helps to create the sense of both movement and stillness which can be seen in the stretch and repose of her muscles.  Image Source: Web Gallery of Art Image Source: Web Gallery of Art This visual dynamic bears many similarities to Michelangelo's unfinished work Slave Awakening (1519-36), which shows the lasting effect Michelangelo had on Rodin's own work. Like Michelangelo, Rodin too tried to “free” his figures from the marble. However unlike Michelangelo, it seems like Rodin also strove to keep his figures intertwined with the stone from which they emerged. Carving in such a way it almost seems that his sculptures could just as easily slip away beneath surface of the marble, as emerge from it. In this regard, there is a physicality to Rodin's work that can be seen in his pieces where Rodin doesn't allow the viewer to forget the medium he works with. Placing the rough hewn stone as both a base and frame for his work. Carved in-the-round, Danaïd is a self contained piece. Unlike others works which stretch out into the space around them, Danaïd huddles into her own space. As such there is little call for her to interact with her surrounding environment, other than the shifting light of the room in which she resides. Danaïd can be appreciated from various angles, encouraging the viewer to circle, however, despite this she remains removed and self contained, her settings making little difference. Bibliography

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCrystal has a MA in the History of Art from Courtauld Institute of Art as well as a BFA in Art History from the Academy of Art University. Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed